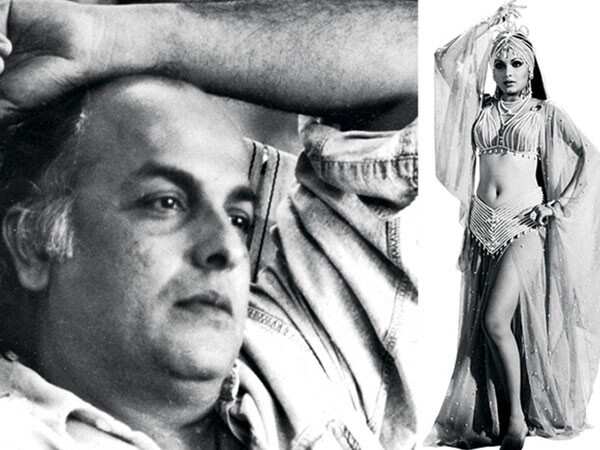

I owe it all to Parveen. - Mahesh Bhatt

Time magazine’s first Indian cover girl, Parveen Babi, falls in love with a flop and worse, married filmmaker Mahesh Bhatt. Naturally, it was an affair consumed by the tabloids. An affair fuelled by flower power, poetry and punk philosophy. A revolt of a romance symbolising the free spirited ’70s! And one day like all unbridled highs it hit a ‘cracking low’. Parveen became a victim of a genetic biochemical disorder – paranoid schizophrenia! While the ‘soft entertainment news’ was busy crucifying Mahesh for being the catalyst to the catastrophe, he was obsessed with keeping her away from the callousness of ‘electric shocks’ and a heartless vocation. But nothing helped. Not even his philosopher friend UG Krishnamurthy who tried in vain to navigate the actress to calmer shores and anonymity. Eventually, Parveen succumbed to psychosis. Mahesh, on the other hand, exorcised the trauma of a ravaged love in his works again and again... right from the semi-autobiographical Arth to the recent Woh Lamhe, films that watermarked his identity as a filmmaker and as a person! Because from the rubble of the relationship he discovered life truths. “Through her I saw the stark face of sorrow and the inevitable end of everything,” confides Mahesh about the woman he lost to insanity decades before he lost to her death... In his words...

THE CRACK-UP

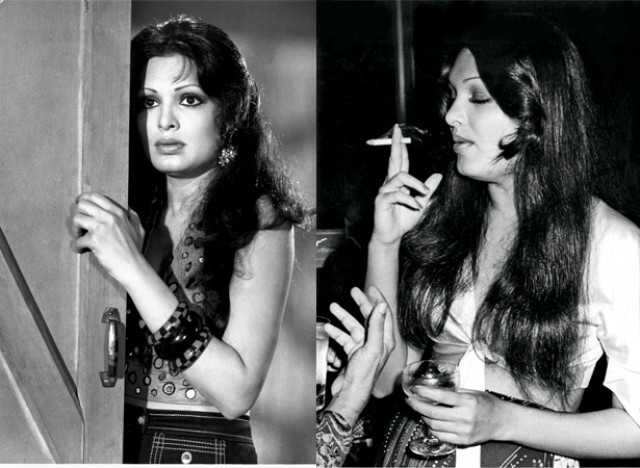

My relationship with Parveen began around 1977. She had returned to India from Italy (after she broke up with Kabir Bedi subsequent to his becoming a sensation in Italy with the TV show Sandokan). She was a top star and was filming for Amar Akbar Anthony (1977) and Kala Pathar (1979) those days, while I was a flop filmmaker. I left my wife Lorraine Bright and my daughter Pooja, who was a kid then, to live in with Parveen. At home she was a traditional girl, who loved to oil her hair and cook - a Gujaratan from Junagadh, albeit with Western influences in her formative years. She was generous and unassuming unlike her diva persona. But she found it stressful to allow the world into her home. She put up a performance when she spoke to producers even on the phone.

Then one day as all bad stories begin… she had a crack-up. It was an evening in 1979. I walked into her Juhu apartment to find her aging mother (Jamal Babi) in the corridor. She said in a whisper, “Look, what’s happened to Parveen!” I walked into that bedroom lined up with innumerable perfumes (the fragrance still lingers in my mind) on the dressing table, to see a sight that sent a chill down my spine. Parveen was dressed in film costume and sat curled up in the corner between the wall and the bed. Her gait was beast like. She had a kitchen knife in her hand. “What are you doing?” I asked. She said, “Shhsssh….! Don’t talk! This room is bugged (installed with a spying device). They’re trying to kill me; they’re going to drop a chandelier on me.” She held my hand and led me outside. I saw her mother look helplessly at me. Her gaze revealed that this episode had happened before; it was not the first time.

From then on began a long night... of fear and trauma. I had to first come to terms with what was happening to her. Several theories floated. One being the ill-informed one that being so successful, she had become a victim of black magic and that an evil spirit had invaded her! I got in touch with well-known psychiatrists, who diagnosed her condition as paranoid schizophrenia (where a person suffers from delusions of fear and persecution), a genetic biochemical disorder. Drug therapy was suggested to keep it on leash. But they warned that if drug therapy didn’t work she’d have to be given electroconvulsive treatment (ECT) (shock therapy in common parlance).

Now began the dance to hide the fact that the diva was down with a mental ailment. At first ‘jaundice’ was used to barricade her from people. I called up Kabir Bedi informing him of her condition. His voice indicated that it was something he was familiar with. He suggested a few hospitals in the UK, which could help her. Danny (Dengzongpa, Parveen’s ex-boyfriend and neighbour) was also helpful. I’d take her to his house to calm her during her panic attacks.

FEAR FACTOR

But the fears hounded her. She was like a storm in a room. Sometimes she’d say the air conditioner had a bug. We had to dismantle it and show it to her. At other times there was ‘a bug’ in the fan or in the perfume... Once we were driving back after meeting my friend, philosopher and guide UG Krishnamurthy, when she said, “There’s a bomb in the car. I can hear it tick!” She threw open the door of the moving car, saying the bomb would burst and ran out on the road with me trying to hold her. People thought ‘Parveen Babi’ was having a fight with her boyfriend. Somehow, I huddled her into a taxi and brought her home.

She also feared that Mr Amitabh Bachchan was out to kill her. Once she accompanied me to Mehboob Studio, saying she wanted to apologise to him. She believed she had harmed him and so had incurred his wrath. Her hallucinations were real for her. At another time, she even confided how during the riots in Ahmedabad (1969), the nuns in her school hid her in a tempo in between mattresses to be taken to a safe zone. She recalled that experience of her body trembling with fear albeit matter-of-factly. Once in the throes of her attack she even told her mother, “Hum nikaah kar lete hain!” She said that thinking marriage would be a safe haven. But I was a married man. There was no way I was going to leave Lorraine. And she was doing too well to give up a career for a nobody like me. Also, it was a nightmare to give her medicines. She’d refuse to have the pills. We’d mix it with the food and drink. But she’d insist, ‘You eat it first!’ At times I did.

Drugs vs Electric shock

She had stayed away from work for too long. So the pressures began for her to return. A huge set had been put up for Shaan (1980) and the foreign technicians were waiting. Some producers wanted to directly talk to the doctors and rightfully so. Loans had been taken on huge interests. Her secretary Ved Sharma, a good man, found it difficult to keep producers away. That’s when doctors suggested electric shocks to make her fall into line. I was opposed to ECT because it doesn’t treat the patient; it caters to society.

When I told her producers that by drawing her into films they were pushing themselves and her towards doom, they dubbed me a ‘user’. Even the media, particularly tabloid journalism, wanted to give the villain a face. They looked for immediate demons citing drugs and a sexually permissive lifestyle as reasons and trivialised her condition. They wanted to prove, ‘Look how the mighty sin and suffer’. I had no legal status in her life or the authority to intervene and say, ‘I’ll not let her be given electric shocks and do irreversible damage to her’. So I ran away with Parveen to UG in Bangalore in September 1979.

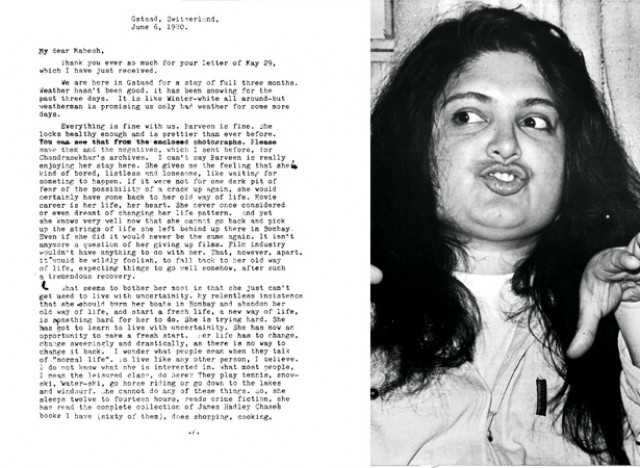

UG & we

I believed the quiet life there would give her solace even as the drug therapy was on. If she had to heal it would be there under the veil of anonymity. UG saw little chance of complete recovery. He suggested an alternative life, free from the pressures of stardom. In October 1979, I left Bangalore and Parveen in charge of UG because he believed I was part of the problem and that I’d have to move away. My presence, he said, was accelerating her end. “She’ll drown you with her. Take hold of your life!” he said. After some time Parveen followed UG to Gstaad, Switzerland. A concerned UG wrote me a letter dated June 6, 1980 from there where he stated, “If it were not for a fear of a crack up again, she’d have certainly gone back… A new way of life is hard for her… I should leave her to her inevitable fate, which is, insanity!” Meanwhile, I had moved back with Lorraine to pick up the threads of life. Lahu Ke Do Rang (1979) had failedI began to write Arth to exorcise the burning charcoals. But the same year Parveen returned to India and into my life once again…

The walkout

… And I went back to her even though I had returned to my wife. Parveen knew I was in touch with UG, who was against her returning to films. He was the voice of sanity, which she didn’t want to hear. So she played the last card... I remember it was the same bedroom. We were about to retire. You may call me an exhibitionist but yes, she wanted to make love. We were close to each other when she said, “Mahesh it’s either me or UG.” I froze and stared at her. She stared back. I didn’t answer. She understood my answer. I saw a tear trickle down her face. I got up and dressed. She said, “Put off the AC it’s cold!” Silence exploded in the room. It was raining outside. I walked through the dark passage. I heard her call, “Mahesh, Mahesh!” I didn’t turn back. Neither did I wait for the lift, fearing she’d come and take me back. I took the stairs instead. I heard her run behind me… stark, bare… I heard her even take a few steps down the stairs… I wanted to run back and tell her, ‘Look, you can’t come out in this state!’ But instead I walked on and out… into the rain.

I understood that the relationship was doomed and that I was deluding myself in hoping for a happy ending. The only person who had cushioned her from ECT, who had nursed her and had suggested a way out; she didn’t want to hear his truth! UG had fathered me and mothered her. There was no way the party would continue. We broke up in 1980.

LAST MEETING

(In 1983, Parveen left for the USA abandoning her projects. She returned in 1989 having put on a lot of weight and was unrecognisable)

I met her again in 1991. It was the days of the Gulf War (August 1990 - February 1991). Saddam Hussain had invaded Kuwait. The CNN channel had started airing the war. Holiday Inn had a TV set where the war was aired round the clock. I’d visit the coffee shop to watch it. There was a book shop there too. One day I was leafing through some books there when I heard a voice, ‘Excuse me!” It sounded intimate. I turned around and saw Parveen up close. But there was no intimacy in her eyes. There was child-like anger instead. She went ahead and asked for the latest issue of the Architectural Digest. They said it was not yet out. She moved past me again and left. For over 11 years, she had ceased to live within me. But this chance encounter stirred those feelings. Nevertheless, we had become ‘intimate strangers’.

THE CLOSURE

(Fourteen years later...)

It was January 22, 2005, I was at the airport, having returned from Hyderabad, when my phone was flooded with SMSes, “Parveen Babi is dead. She was found dead in her apartment (due to diabetic complications).” It seemed unreal. I learnt that her body was lying unclaimed at the Cooper Hospital. I thought if none of her relatives came forward I’d bury her. She was the springboard of my success. Arth (based on his relationship with Parveen) became the lifeblood of my resurrection. You take away this defining watershed tragedy and my narrative ceases to exist. I owe it all to her. By offering to bury her I felt a sense of closure. As they were laying her to rest on January 23, 2005, I wondered what I’d have been without this woman. She had brought some ‘arth’ to my existence!

Post a Comment